DNA DAMAGE

DNA damage, due to environmental factors and normal metabolic processes inside the cell, occurs at a rate of 1,000 to 1,000,000 molecular lesions per cell per day. While this constitutes only 0.000165% of the human genome’s approximately 6 billion bases (3 billion base pairs), if left unrepaired can cause mutations in critical genes (such as tumor suppressor genes) can impede a cell’s ability to carry out its function and appreciably increase the likelihood of tumor formation and disease states such as cancer.

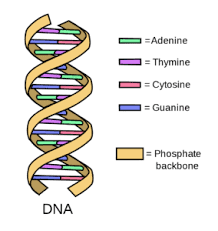

The vast majority of DNA damage affects the primary structure of the double helix; that is, the bases themselves are chemically modified. These modifications can, in turn, disrupt the molecules’ regular helical structure by introducing non-native chemical bonds or bulky adducts that do not fit in the standard double helix. Unlike proteins and RNA, DNA usually lacks tertiary structure and therefore damage or disturbance does not occur at that level. DNA is, however, supercoiled and wound around “packaging” proteins called histones (in eukaryotes), and both superstructures are vulnerable to the effects of DNA damage.

There are several types of DNA damage that can occur due either to normal cellular processes or due to the environmental exposure of cells to DNA damaging agents. DNA bases can be damaged by: (1) oxidative processes, (2) alkylation of bases, (3) base loss caused by the hydrolysis of bases, (4) bulky adduct formation, (5) DNA crosslinking, and (6) DNA strand breaks, including single and double stranded breaks. An overview of these types of damage are described below.

Oxidative Damage

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can cause significant cellular stress and damage including the oxidative damage of DNA. Hydroxyl radicals (•OH) are one of the most reactive and electrophilic of the ROS and can be produced by ultraviolet and ionizing radiations or from other radicals arising from enzymatic reactions. The •OH can cause the formation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG) from guanine residues, among other oxidative products (Figure 12.4). Guanine is the most easily oxidized of the nucleic acid bases, because it has the lowest ionization potential among the DNA bases. The 8-oxo-dG is one of the most abundant DNA lesions, and it considered as a biomarker of oxidative stress. It has been estimated that up to 100,000 8-oxo-dG lesions can occur daily in DNA per cell. The reduction potential of 8-oxo-dG is even lower (0.74 V vs. NHE) than that of guanosine (1.29 V vs NHE). Therefore, it can be further oxidized creating a variety of secondary oxidation products.

Alkylation of Bases

Alkylating agents are widespread in the environment and are also produced endogenously, as by-products of cellular metabolism. They introduce lesions into DNA or RNA bases that can be cytotoxic, mutagenic, or neutral to the cell. Figure 12.6 depicts the major reactive sites on the DNA bases that are susceptible to alkylation. Cytotoxic lesions block replication, interrupt transcription, or signal the activation of apoptosis, whereas mutagenic ones are miscoding and cause mutations in newly synthesized DNA.The most common type of alkylation is methylaton with the major products including N7-methylguanine (7meG), N3-methyladenine (3meA), and O6-methylguanine (O6meG). Smaller amounts methylation also occurs on other DNA bases, and include the formation of N1-methyladenine (1meA), N3-methylcytosine (3meC), O4-methylthymine (O4meT), and methyl phosphotriesters (MPT).

Base Loss

An AP site (apurinic/apyrimidinic site), also known as an abasic site, is a location in DNA (also in RNA but much less likely) that has neither a purine nor a pyrimidine base, either spontaneously or due to DNA damage (Figure 12.7). It has been estimated that under physiological conditions 10,000 apurinic sites and 500 apyrimidinic may be generated in a cell daily.

DNA Strand Breaks

Ionizing radiation such as that created by radioactive decay or in cosmic rays causes breaks in DNA strands (Figure 12.10a). Low-level ionizing radiation may induce irreparable DNA damage (leading to replicational and transcriptional errors needed for neoplasia or may trigger viral interactions) leading to premature aging and cancer. Chemical agents that form crosslinks within the DNA, especially interstrand crosslinks, can also lead to DNA strand breaks if the damaged DNA undergoes DNA replication. Crosslinked DNA can cause topoisomerase enzymes to stall in the transition state when the DNA backbone is in the cleaved state. Instead of relieving supercoiling and resealing the backbone, the stalled topoisomerase remains covalently linked to the DNA in a process called abortive catalysis. This leads to the formation of a single stranded break in the case of Top1 enzymes or double stranded breaks in the case of Top2 enzymes. DNA double strand breaks due to topoisomerase stalling can also occur during the transcription of DNA (Figure 12.11). In fact, abortive catalysis and the formation of DNA strand breaks during transcriptional events may serve as a damage sensor within the cell and help to instigate DNA damage response signaling pathways that initiate DNA repair processes.

Featured

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment